I’ve translated this article from the one I wrote in French with the help of Magistral ;) Cocoricooo !

Everything is Software Link to heading

This article follows my previous one: Everything is a Computer, but it is not essential to have read it to understand this one.

In this article, I will talk about a realization that is mostly linguistic: I realized that there are quite a few words that designate more or less the same thing but with nuances that I struggled to discern.

- Code

- Algorithm

- Program

- Script

- Software

- Application

One of the difficulties in understanding information technology is the degree of abstraction of what we are talking about. There are several levels of description that we can approach, and each has interesting properties.

In this blog post, I would like to make several things clear: first, the notion of implementation, moving from an idea in theory and implementing it in practice. Then, I would like to give you a feel for the notion of nesting, using something we have already done and nesting it within something else instead of starting all over again.

Analogy with Cooking Link to heading

So let’s get to it, an algorithm is like a cooking recipe.

When I say “cooking recipe”, I think especially of grandmothers’ recipes, those that are passed down from generation to generation, you may have inherited a gratin or tartiflette recipe from one of your grandparents ;)

The recipe generally tells you how to make the dish in question. It gives you the ingredients (potatoes, onions, bacon, etc.), the basic actions (dice, slice, sauté), tells you actions to perform (place the camembert on the potatoes), conditions to respect (as soon as the onions are well browned, take out of the oven) etc.

The purpose of the cooking recipe is to give the idea of how to make a dish or a meal, at a relatively high level of abstraction.

Implementation Link to heading

Once we have the recipe, we can implement it at home: we try to reproduce it simply. But when the recipe says “peel”, it doesn’t specify whether it’s with a knife, with a peeler, or various other tools. When it says “sauté”, it doesn’t necessarily specify whether it’s in a frying pan, in a saucepan, or in a wok.

It’s up to you to make these choices, it’s up to you to choose how you implement the recipe in your kitchen or in someone else’s. And we can easily imagine that making the same recipe in the kitchen of an Italian restaurant won’t be the same as in a Vietnamese restaurant or in a Lebanese restaurant: the tools will be different, and the way of managing time or cooking may not be the same.

All this was not specified in the recipe because the recipe gives the idea of the dish in such a way that we can reproduce it almost anywhere, in any kitchen.

We could imagine a foolish cook, incapable of implementing a recipe. Perfectly capable of following precise instructions, but not at all autonomous and lost as soon as the instructions are vague or ambiguous. In this case, it would be possible to write a kind of “very precise recipe”, pre-implemented for a particular kitchen or environment.

The foolish cook is the analogy of a computer, or rather a computer processor. The “very precise recipe” is the analogy of computer code, but we’ll come back to that right after!

If the recipe is too imprecise or gives inconsistent instructions (such as: “brown the onions then peel them”, “add flour until you get a very liquid dough”, “mix the 2 potatoes until you get 3”), the cook would be forced to stop.

Nesting Link to heading

Now, imagine you are writing a cookbook. On the first pages, you explain how to make a great tomato sauce. Imagine that in the following pages you want to give the recipe for bolognaise sauce, which is, roughly, tomato sauce with ground meat and a few more spices (I’m bad at cooking so I can say that). You won’t rewrite the tomato sauce recipe in the bolognaise sauce recipe, you’ll simply give the reference to the initial tomato sauce, and complete it to make a bolognaise.

The tomato sauce recipe is therefore “nested” within the bolognaise one, we can “call” it. Similarly, we could imagine a pizza with bolognaise on top (am I making you smile with my grotesque recipes?), and we won’t rewrite the bolognaise sauce recipe or the tomato sauce recipe, we’ll simply give the references. So we have a bolognaise pizza recipe that calls the bolognaise sauce recipe which itself calls the tomato sauce recipe. Nesting is potentially infinite!

Back to Computing Link to heading

We find the concepts of implementation and nesting in the world of computing, and that’s precisely what is key to differentiating the terms mentioned above.

An algorithm is like a cooking recipe, it’s the abstract idea of a sequence of operations that can be performed to obtain a certain result.

A program or a script is the implementation of an algorithm in a particular environment, moving from an abstract idea to a concrete execution.

A computer blindly applies what we tell it in the form of code in the same way that a foolish cook would blindly apply the “very precise recipe” adapted to a particular environment. In fact, if you understood my article on computers, you will surely understand that when I say “computer”, I mostly mean “processor” (or CPU), because it is this electronic component that performs operations.

A software, an application or the software, is also initially an abstract idea of a sequence of operations, but which generally aims to be used directly by a user and which will therefore need to be very complete.

For example, the application must be available and work on both computer and phone, we must consider all screen sizes, we must program the display so that it is fluid and easily understandable, and of course we must anticipate all bugs and fix them!

To navigate such a project, the notion of nesting is absolutely essential, we code the basic functionalities and then build, on top of them, more interesting but complex functionalities.

The Algorithm of Social Networks Link to heading

I wanted to add a small paragraph about the use of the word “algorithm” in the context of social networks:

Thanks to Nitter for saving me from browsing X ;)

In the mouths of these politicians, this term refers mostly to the way social networks recommend content to their users. In reality, Instagram, TikTok, Twitch, etc. have developed a complex set of programs (a software, in fact) that often involves AI (a vast subject, I’ll probably talk about it in the future) taking as input the behavior of a user (likes, posts but especially time spent on each content) and which gives, as output, a proposal of content to show to this user.

These “algorithms” are indeed implemented in reality, so we should rather speak of “programs” or “software” according to our definitions. However, each platform has its own particular software coded in its own way, although the objective and the result are the same: to recommend content to users based on their behavior.

These politicians were surely not talking about a software for recommending content on a particular platform, they were denouncing all the software on all platforms. They were denouncing the abstract idea of a software that recommends content based on behavior. But as we said earlier, we call the abstract idea of a program an algorithm.

We have now defined all the complicated terms, you can stop here if you want to stay on theory! But I know that back at the time, I would have liked to have concrete examples.

What does this “code” look like? How to do nesting and implementation concretely?

If you are also curious to know, follow me in the next part ;)

Concrete Examples with Python Link to heading

Unlike cooking recipes, which are written in normal language (which we call natural language in computer science), computers do not support its nuance and ambiguity. The only way we can transmit instructions to a computer is in a very formal and restricted language called a programming language. We designate a “sentence” in this language as “code”.

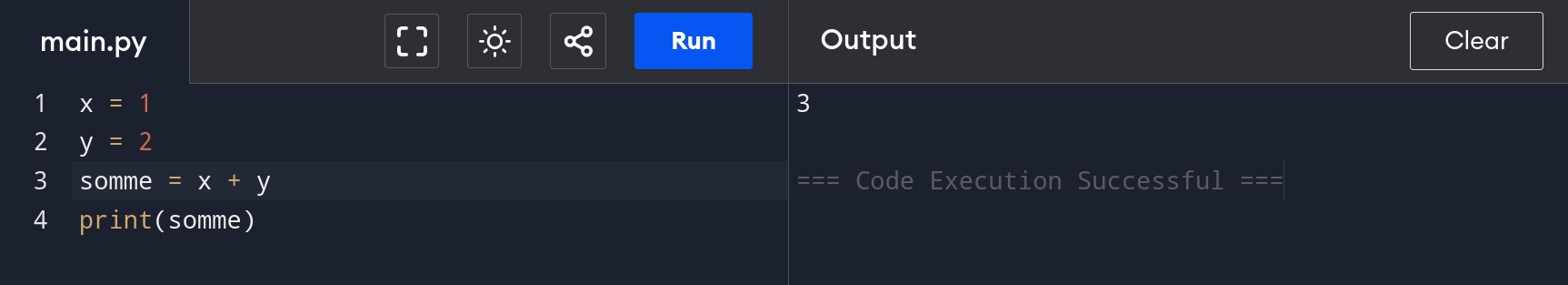

There are several programming languages in which we write programs or scripts. Here is a program in the Python language, which is one of the most popular, see if you can understand what is happening:

x = 1

y = 2

somme = x + y

print(somme)

At first glance, the program above should be quite understandable. It is a program in which we declare two variables: x and y, we declare a third variable somme (“sum” in French) to which we assign the value x + y. Finally, we display on the screen the value of somme, which, as you might expect, will be 3.

You can verify this result yourself in two ways:

- Install the Python programming language on your computer, use a text editor (like Notepad on Windows), copy and paste the program above and save the file with a

.pyextension likeprogram.py, double-click on it and see the result. - Go to this site, copy and paste the code on one side, run it and see the result on the other side, as shown below:

You can then try with different values for x and y and see the results.

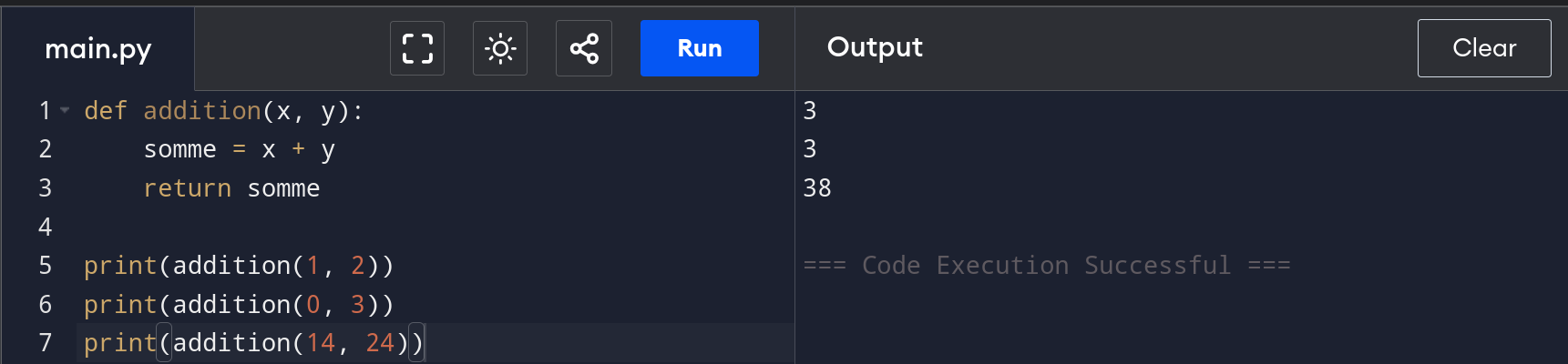

Let’s now see a Python feature that allows us to do this in a slightly more practical way:

def addition(x, y):

somme = x + y

return somme

print(addition(1, 2))

print(addition(0, 3))

print(addition(14, 24))

Explanations:

deftells the computer that it is about to define a program that takes something as input and outputs something.additionis the name of this program.(x, y)tells the computer that it should expect to receive 2 numbers as input.somme = x + yquite explicitly, this line tells the computer that it must assign to a new variablesommethe resulting value of the operationx + y.return sommethis line tells the computer that it must return the variablesommeto the user and stop executing the program we have defined. If by mistake, the coder added lines of code after this one, they would quickly see that they are not executed.addition(1, 2)executes the program for a value ofxof 1 and a value ofyof 2 and returns the result.print(addition(1, 2))displays the result of the previous program.

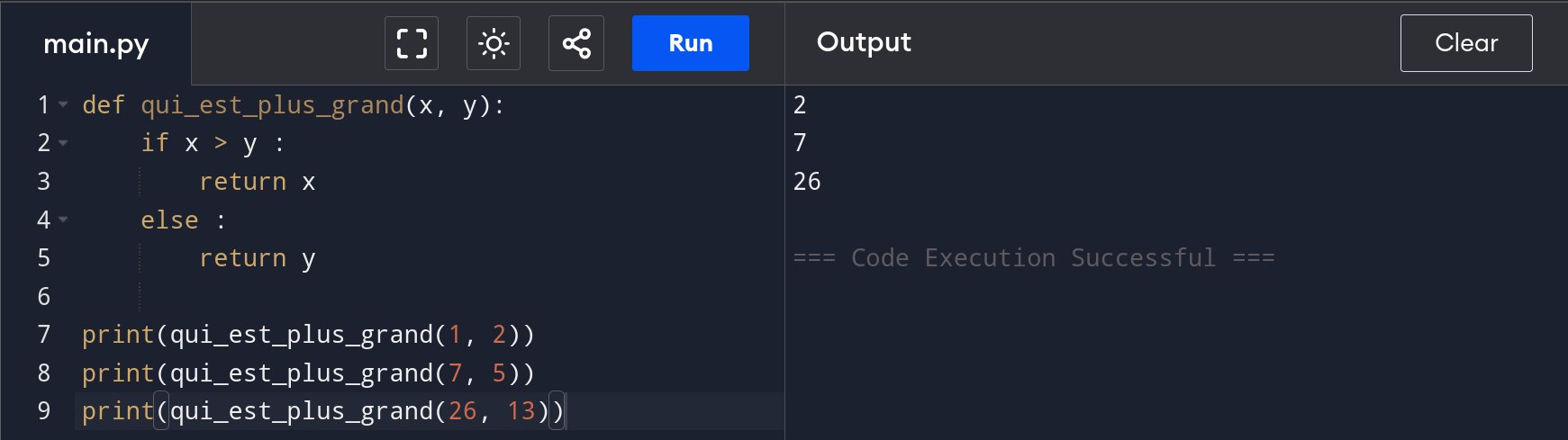

Let’s look at this one:

def qui_est_plus_grand(x, y):

if x > y :

return x

else :

return y

print(qui_est_plus_grand(1, 2))

print(qui_est_plus_grand(7, 5))

print(qui_est_plus_grand(26, 13))

Note the indentations after the : characters. I hope you’re not lost!

Explanations:

def qui_est_plus_grand(x, y):we define a program with the namequi_est_plus_grand(“who’s taller” in French) that takes 2 variables as input.if x > y:this line corresponds to a condition that the computer will check to see if it is satisfied or not. If yes, it does what is indented afterwards.return xis the action that the computer performs if indeedxis greater thany. It returnsxto the user.else:is used to specify what the computer should do ifxis not greater thanyand therefore the linereturn xis not executed.return yis what is executed when the condition of theif, namely thatx > y, is not satisfied.

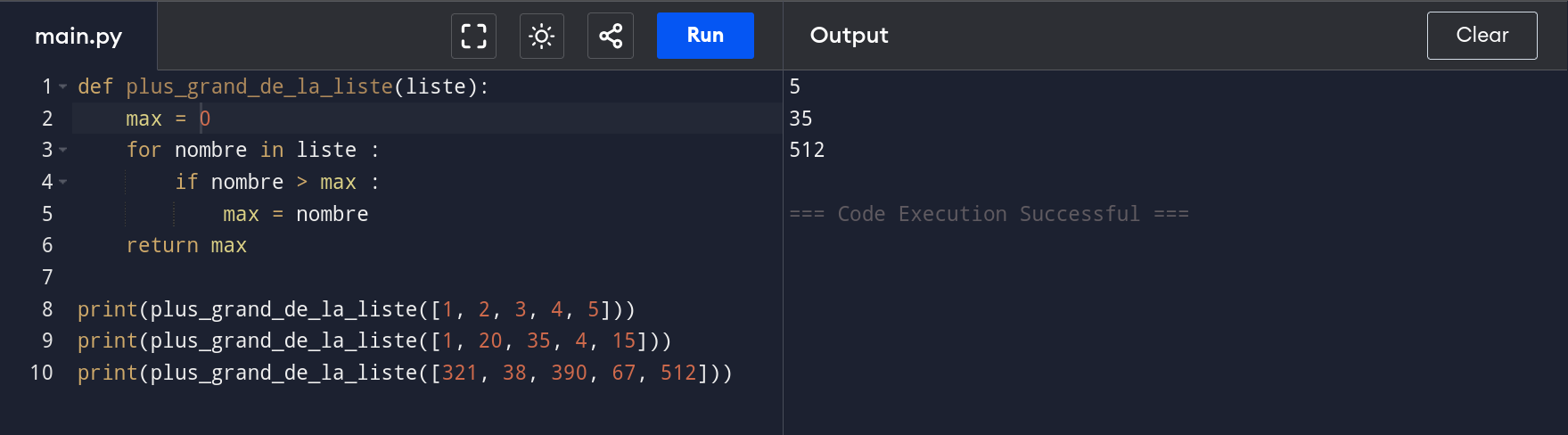

Python also allows us to introduce lists in the following form: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The following program shows one way to manipulate them:

def plus_grand_de_la_liste(liste):

max = 0

for nombre in liste :

if nombre > max :

max = nombre

return max

print(plus_grand_de_la_liste([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]))

print(plus_grand_de_la_liste([1, 20, 35, 4, 15]))

print(plus_grand_de_la_liste([321, 38, 390, 67, 512]))

Believe it or not, this program takes a list of numbers as input and returns the largest number in the list.

Explanations of the program above:

- The keyword

defwhich indicates that we are defining a program. plus_grand_de_la_liste(“tallest of the list” in French) is the title (rather explicit) of the algorithm.listeis what the program takes as input.max = 0we assign the value of 0 to the variablemax.for nombre in liste:for each element in the list, we will perform the action described in everything that is indented relative to this line. This is called aforloop.if nombre > max :we check if the element in the list is greater than the variablemax. If yes, we perform the action defined next, if no, we do nothing. This is called a conditional action.return maxnote that this line is not indented relative to the three lines above, so it is not part of this loop. It returns the variablemax.

Nesting Example Link to heading

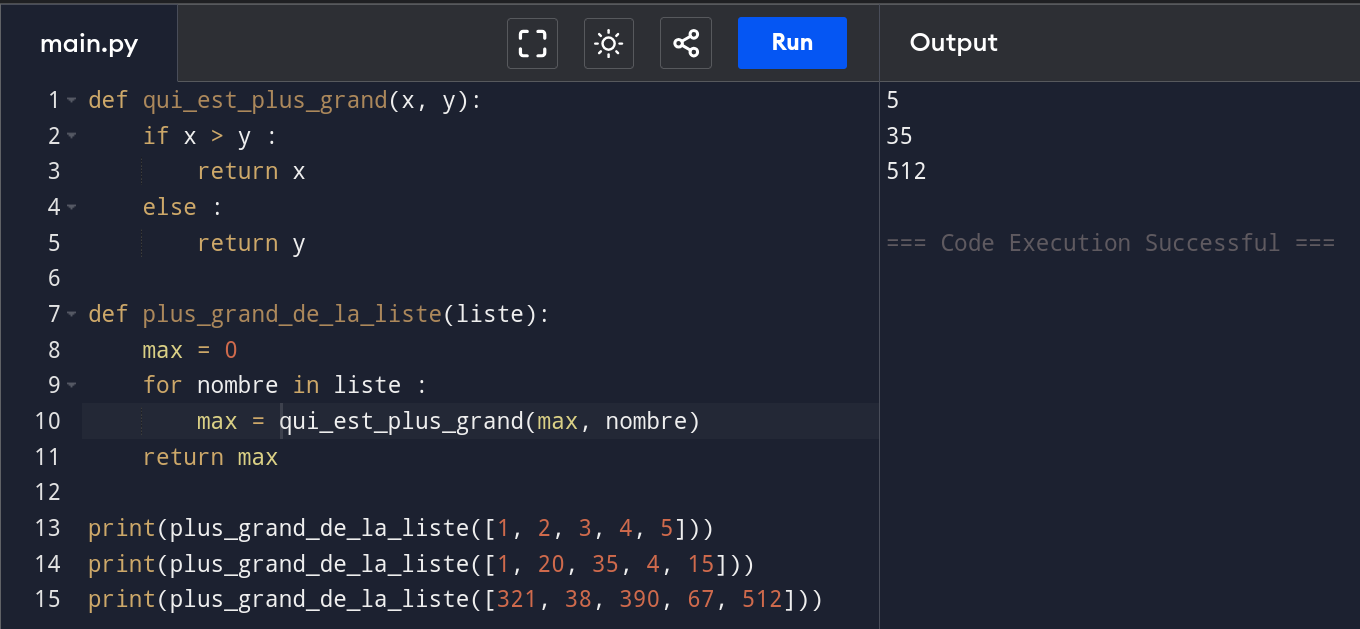

If you understood the program above, you will then understand why we could easily nest the qui_est_plus_grand function within plus_grand_de_la_liste:

def plus_grand_de_la_liste(liste):

max = 0

for nombre in liste :

max = qui_est_plus_grand(max, nombre)

return max

Indeed, comparing two numbers and finding the largest one, we have already done that in a function, so why bother? Let’s nest! Computing is a discipline of lazy people if you hadn’t understood, we spend our time asking computers to work for us!

Implementation Example Link to heading

We used Python above, but there are many other programming languages. Let’s take our plus_grand_de_la_liste program in other languages to see what it looks like, I will use codeconvert.ai for that.

Here it is in JavaScript, a language mainly useful for coding websites:

function plusGrandDeLaListe(liste) {

let max = liste[0];

for (const nombre of liste) {

if (nombre > max) {

max = nombre;

}

}

return max;

}

This is quite different, we see that there are many more parentheses, there are terms like let or const that have been added, but we recognize the for, the if, etc.

Here it is in Bash, a language widely used to talk to Linux computers:

#!/bin/bash

plus_grand_de_la_liste() {

local liste=("$@")

local max=${liste[0]}

for nombre in "${liste[@]}"; do

if (( nombre > max )); then

max=$nombre

fi

done

echo $max

}

We note an extra line at the beginning, we also see that the inputs of the program are given differently, we also see that we need the keywords if and fi to indicate what is included in the conditional action, similarly we need do and done to indicate what happens in the for loop.

Now, we can see that the programs above, in all these programming languages are different, but they all have something in common: they implement the same algorithm. This algorithm is the more abstract idea of a sequence of operations that would take a list of numbers and find the largest number in it.

With our few examples, we have some idea of how to talk to a computer. Like grandmothers’ recipes, we could explain this algorithm and then implement it with Python, JavaScript or Bash.

Generally, we do this in a language called pseudo-code, and here is what the pseudo-code of the plus_grand_de_la_liste program would look like:

ALGORITHM plus_grand_de_la_liste:

TAKE AS INPUT: a list of numbers

RETURN AS OUTPUT: a number

ASSIGN the 1st element of the list to the variable max

FOR EACH element in the list:

IF element is greater than max:

ASSIGN element to max

END IF

END FOR

RETURN max

Summary Link to heading

So to summarize, we start with an algorithm, which we imagine and define, potentially in pseudo-code, then we implement it with code in a programming language to obtain a program or a script. To achieve an efficient increase in complexity and obtain a software or an application (software in English), it is very useful to use nesting by reusing programs within other programs to avoid having to re-code them and to correct errors and bugs more easily.

Conclusion Link to heading

I thought a lot about how to present these concepts in the clearest and most pedagogical way possible, and I went back and forth several times with some of my loved ones to refine the text, find the difficult points to understand, find meaningful and stimulating examples, and give coherence to the whole article. I hope that I (or rather we) have succeeded well and that you have learned or clarified things!

See you soon for the next post, where we will talk about data transfer ;)