I’ve recently come to realize that people who are very comfortable with computers are likely those born during a specific period. Too early, and they wouldn’t have had a computer at home during their childhood; too late, and they would have had a smartphone instead.

I’m sure this would make for an interesting topic, but I don’t have time to explore it further today. In any case, I clearly identify with the latter category. I remember having an iPod Touch (basically an iPhone without a SIM card) long before I had anything else. And as I discuss in My Setup, it took me quite a while to really get a handle on computers.

As I’ve progressed in my skills in the field of information technology, there have been three particular realizations that have profoundly changed the way I think about this technology and how I approach its problems.

Perhaps I was particularly ignorant, and this is common knowledge that’s obvious to almost everyone, but based on the discussions I have with my loved ones, I’d be surprised. That’s why I think it’s still worth writing this blog post. I won’t just be writing one post; I’ll actually be writing three, and this will be the first one.

Everything is a Computer Link to heading

Back then, I had the impression that there were things called “servers,” “desktop” or “laptop” computers, sometimes referred to as “Macs” or “PCs,” not to mention “tablets” and “smartphones”! I found all these terms very confusing, and this confusion surrounding the language we still use today to describe information technology is, in my opinion, a hindrance to learning.

The first realization was that, in fact, everything was indeed a computer. There was no fundamental difference between a laptop, a desktop computer, a smartphone, Google’s servers, industrial systems that manage hundreds of machines on a production line, and the onboard computer of a fighter jet.

All these systems have the same architecture: a processor (CPU), RAM, and storage memory. The next three chapters will explain each component.

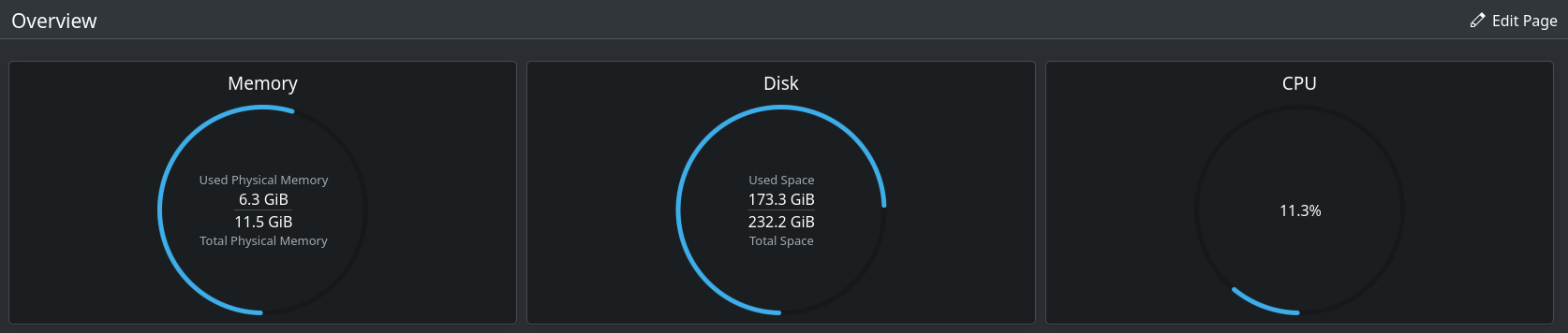

Here’s the dashboard of my computer; you can clearly see the components.

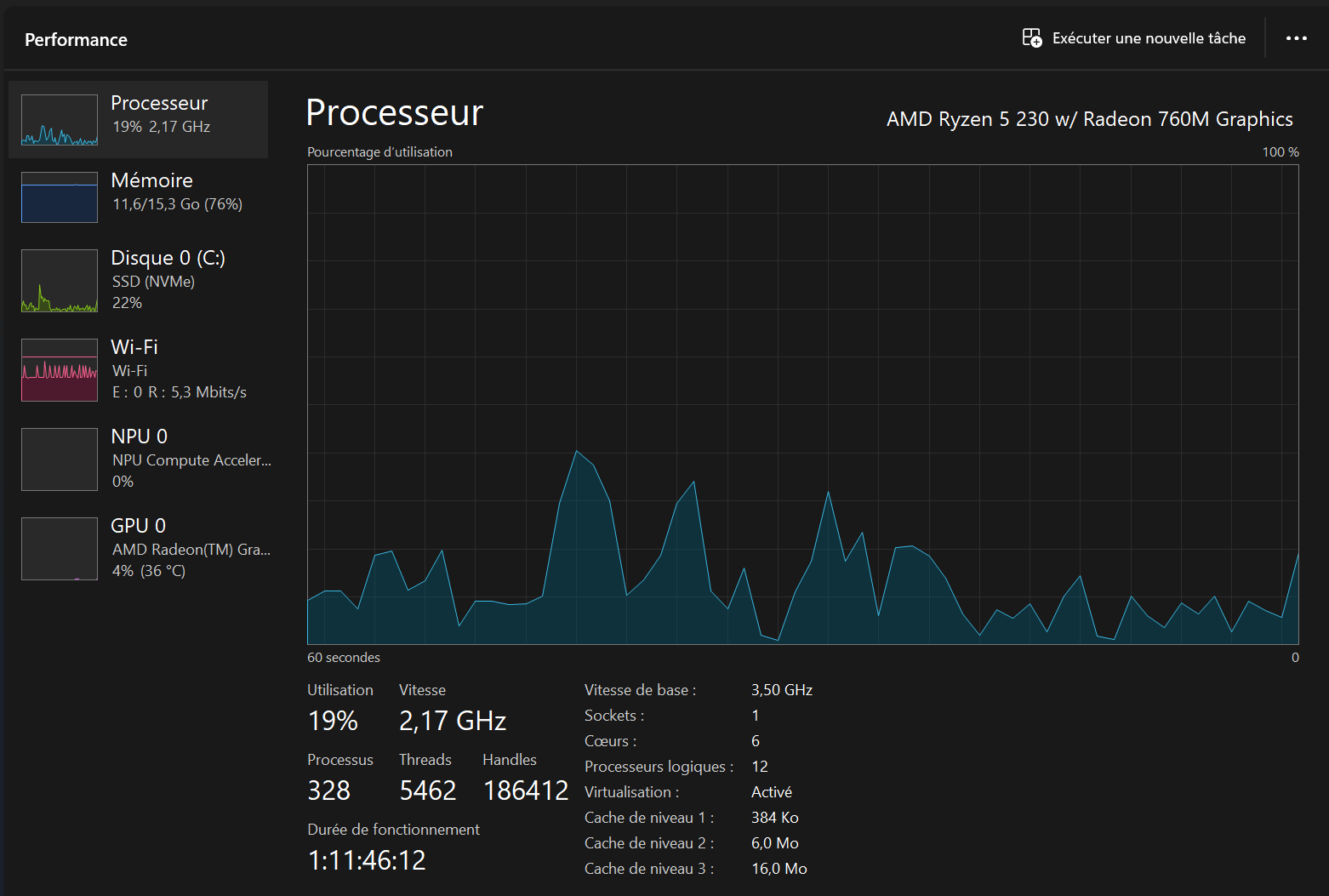

Same thing on this Windows PC, with Wi-Fi, a GPU, and an NPU.

CPU vs. GPU vs. TPU Link to heading

CPU Link to heading

The first component is the heart of the machine: it’s what does the calculations. It’s the component that performs operations. It’s an acronym for Central Processing Unit, and it’s what heats up when you ask your computer to perform calculations, read an audio or video file, or copy photos to a hard drive. Generally, your CPU is placed on an electronic assembly called a “motherboard,” of which it’s the main element. The motherboard typically has the task of starting the computer correctly and ensuring that all electronic components can communicate with each other.

If you’ve ever shopped for a laptop, you’ve probably heard stories about Core-i5, Core-i7 for Windows computers, and maybe also M1, M2 Pro, R1, etc. chips for Apple Macs. These are simply processors with some differences in architecture and compatibility.

Typically, when your CPU is overwhelmed, your fans will spin at full blast, your mouse cursor will start moving in jerky, uneven bursts before freezing entirely. Input devices (like your keyboard or mouse) should stop responding altogether. Other processes might still keep running, though, if they haven’t received a shutdown command yet. (And since nothing’s responding, you can’t send that command!)

Some computers have built-in safeguards to prevent the CPU from hitting 100% capacity, which might force all processes to halt. If that’s not the case, you could wait it out, but I’d strongly recommend hard-shutting down the PC instead to minimize damage to the CPU. Running at full throttle nonstop will accelerate wear and tear on the components.

GPU Link to heading

Now, you may know that there are GPUs (Graphics Processing Unit). These are very specific electronic components that fundamentally do the same thing as a CPU. The differences are:

- A CPU is very versatile; it can perform any type of task, including the most complex ones.

- A GPU is architecturally designed to perform the same type of operation on a lot of data in parallel.

Some calculations are very parallelizable, such as decoding a video file to display it on a screen (hence the name Graphics), but also, and especially right now, training AI models, which generally involves performing a huge number of additions and multiplications.

Other calculations are much less parallelizable because they’re very sequential, such as loading a web page: you send a request, wait for the response, and then send another one, etc.

To give you an idea of the size of a graphics card ;)

A GPU is to a graphics card what a CPU is to a motherboard. A graphics card contains the GPU as well as other electronic components. We can see that it’s still quite large and needs big fans to cool it down significantly. This is the form in which we can really push the performance of a GPU.

However, as you’ve seen in the Windows Task Manager screenshot above, it’s possible to integrate a GPU into laptops; they’ll be less powerful in this form, but they’ll still be able to lighten the CPU’s load for simple tasks like displaying graphics.

TPU Link to heading

Now, you may have seen the mention of TPUs (Tensor Processing Unit).

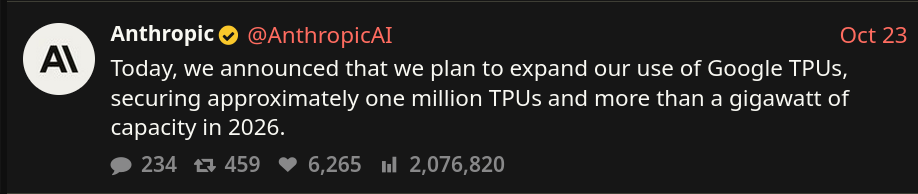

Yes, TPUs consume a lot…

These are electronic components developed by Google that are part of a large family (TPU, NPU, AI accelerators, etc.); these components are even more specialized in training AI models because they perform many additions and multiplications very efficiently.

RAM Link to heading

RAM, or Random Access Memory, is also called working memory or volatile memory. It’s a type of memory with which the processor interacts quickly (reading, writing, modifying data, etc.), but it’s ephemeral/volatile: as soon as the computer is turned off, the information it contains disappears.

RAM is generally composed of sticks in DDR4, DDR5, etc. formats that are plugged directly into the motherboard (where the processor is located, if you recall!).

If your RAM is saturated, you’ll still be able to move your mouse and use your keyboard—but good luck interacting with your apps. Opening them? Closing them? Pausing that video that’s still playing in the background? Nope. (Though you can try clicking frantically, it won’t help, but it might make you feel better. ;))

Usually, you can close applications but not from the apps themselves. Instead, you’ll need to use the Task Manager (or macOS’s “Force Quit” option), depending on how easily your system lets you access it.

The real fix for RAM hitting 100% too often? Just buy more RAM. Personally, I get by fine with 12GB, though I do occasionally close apps when I feel my PC inching toward disaster. (Better safe than sorry!)

Storage Memory Link to heading

We refer to storage memory (or long-term memory, or simply “storage”) to describe the information that persists even when the computer is turned off. When you save a file, it’s written to this storage memory so that you’ll find it again after a reboot, a battery change, etc.

This memory is encoded on components that react more slowly, and the information in storage memory is sometimes copied to RAM so that the processor can access it more quickly.

The formats are HDD (Hard Drive Disk), SSD (Solid-State Drive), USB sticks, and SD cards, etc.

This is the memory that’s indicated in GB on iPhone technical specifications.

A small note on the term “ROM.” It’s an acronym for Read-Only Memory, and it’s a type of memory intended to be read but not modified. It’s non-volatile, and we find it on certain components of the motherboard (yes, the motherboard again!). However, it’s not the storage memory of your computer, since that memory is often modified when you add or remove files.

Conclusion Link to heading

What I find enlightening is considering that any content you can access permanently is stored on storage memory somewhere physically on Earth. In theory, it would be possible to find the precise geographical location of your data, or rather the hard drives on which they’re stored. On the memory of your devices or the hard drives of the digital service companies (Google Drive, Microsoft OneDrive, Apple iCloud, etc.) you use. The “Cloud” is just a somewhat fuzzy term that refers to a complex network of storage memory owned and maintained by a company.

I invite you to consider that this applies to all the messages you’ve sent on messaging apps, as long as you still have access to them. Your conversations and all associated attachments are stored on a hard drive somewhere on Earth.

As all aspects of our lives become increasingly digital, it’s imperative to regain control over our personal data, which too often ends up in the hands of companies that act more like giant advertising agencies than digital services.

Learn that there are alternatives to leaving your data with these large companies, that you can choose more respectful companies, and that you can even find local solutions at home by repurposing old computers. I’ll probably write an article about this someday.

Thanks for reading, and see you in my next post, which will be about software!